Reading our entries

A few explanations and recommendations to guide your exploration of CCC entries:

- Reference system: the CCC uses ESTC reference numbers by default but also offers the corresponding citations in the Wing Short Title Catalogue (2d edition, 1996).

- Dates and locations: the information was imported from the ESTC, and we are aware that there is some uncertainty around that kind of data. For dates, where the ESTC offered alternative printing dates, we have included them (in brackets) in the ‘Year’ field. For uncertain locations, or cases of false imprints, however, we decided to enter the location suggested by the ESTC in the ‘Location’ field and corresponding menu. When searching printing locations, therefore, we recommend that you also consult the ‘Imprint’ field to identify additional information that would not be reflected in ‘Location’.

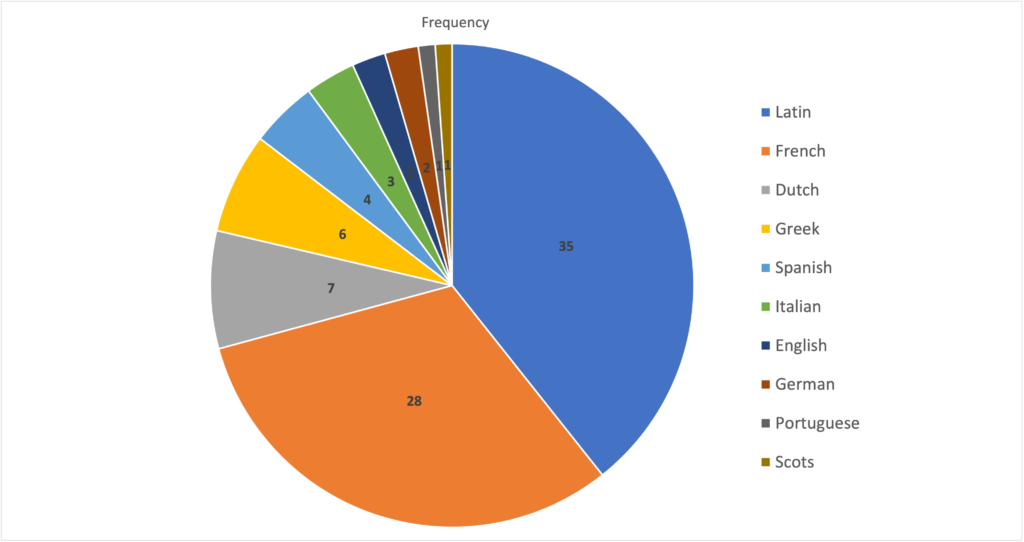

- Languages: our data on source, mediating, and target languages has been gathered in part from the ESTC, but mainly through the information contained in the translated books themselves (titles, prefaces, etc.). Although we have done our best to document these fields, a certain amount of uncertainty is to be expected – particularly around cases of indirect, or so-called ‘second-hand’ translations, which can be particularly difficult to identify.

- EEBO: the ‘EEBO’ field indicates whether there are digitized copies of a given title, and if so, which libraries have contributed their copies. Please note that EEBO keeps adding new image sets to its database, so you might want to check if an entry marked here as ‘not available’ has perhaps been added to EEBO since.

- Paratexts: the information entered in that field is copy-specific, that is, based on the individual copies digitized on EEBO. Variations are documented in the ‘Notes on translation’ field.

There is great variety in the ways early modern authors, translators and stationers used the liminary spaces of the printed book. In our descriptions, we have sought to achieve a certain degree of systematicity, while still reflecting the diverse and complex practices documented in the archive. Here are few remarks and guidelines:- Discursive paratexts: besides providing information on prefaces, postfaces, etc., this field also identifies the dedicatees and ‘friends’ of translators and their printers. Prefaces and postfaces are mentioned as such. To find patrons and friends, look for ‘dedication’ or ‘dedicatory epistle’. Encomiastic pieces, or praises of the author, or translator, are called ‘laudatory’ verse or prose. We have done our best to specify if liminary texts were penned by authors (translated), translators, or stationers. If you are interested in documenting various forms of address to the reader, we recommend that you enter ‘reader’ in the search field.

- Organizational paratexts: look for ‘index/indices’, ‘contents’; ‘glossary’; ‘table’; ‘chart’; ‘but also ‘argument’, ‘caption title’, ‘running title’, and ‘printed marginal notes’.

- Visual paratexts: Look for ‘illustration’, ‘frontispiece’, ‘portrait’, ‘map’. We distinguish between ‘illustrated’ and ‘decorated’ title pages depending on whether they feature a full-page illustration or more limited visual decorations. The catalogue also documents decorative headpieces and tailpieces; decorative or historiated initials; flowers, knots and friezes; as well as printers’ devices or marks. Please use these keywords for best results.

- Promotional paratexts: some printed translations include lists of books sold by the stationer. These are termed ‘advertisements’ in the catalogue — not to be mixed up with prefatorial ‘advertisements to the reader’ — avis au lecteur— which are here entered under the term, ‘address to the reader’.

- Notes on translation: among the various notes on font, layout, print variants, you will find information on readers’ marks found on the volumes digitized on EEBO. ‘Annotation’ refers to any kind of intervention (from marginal writing to undescoring, manicules, or even doodles). ‘Inscription’ usually indicates a name (legible or not), sometimes accompanied by a date. While we have done our best to document what we saw on the pages of the printed books, we could naturally not be exhaustive: our catalogue does not replace the consultation of printed copies, either in digitized form or in their physical materiality.

Visualizing our data

You will find a number of visualizations (as charts, maps, and graphs) under Facts and Figures and Networks and Maps.

You may also want to generate your own visualizations, based on the whole dataset (details below) or your own selection of extracted data.

One of the most accessible, open-access visualization platforms is Stanford University’s Palladio. Our data is structured in a way that may easily be adapted to generate network graphs and maps. Detailed information on how to prepare data and use Palladio’s visualization tools is available on the platform. You will find a more advanced tutorial by Marten Düring on the Programming Historian website.

Another useful, open-access online tool for network visualization is John Ladd’s Network Navigator (tutorial here).

Re-using and citing our dataset

You can download the complete catalogue from our HSS Commons repository and extract data from our tables in .csv format.

Please cite: Belle, Marie-Alice, Brenda M. Hosington et al. (2025), “Cultural Crosscurrents Catalogue Dataset: Printed Translations in Britain 1641-1660”, HSSCommons: (DOI: 10.25547/Y355-8V96)

Our data is held under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

Our catalogue data is largely based on the English Short Title Catalogue. ESTC records are freely available without license. We provide ESTC numbers for each CCC entry for the sake of transparency and to facilitate cross-referencing.