The Cultural Crosscurrents Catalogue of Printed Translations in Stuart and Commonwealth Britain (1641-1660) (CCC) was initially created as a complement to Brenda M. Hosington’s Renaissance Cultural Crossroads Catalogue of Printed Translations in Britain (1473-1640) (RCCC).

Currently featuring over 1700 entries, the Cultural Crosscurrents Catalogue gathers translations in all and into all languages printed in England, Scotland, Ireland, and ‘New England’, or translations printed abroad but in English, for the two decades covering the English Civil Wars and the Interregnum.

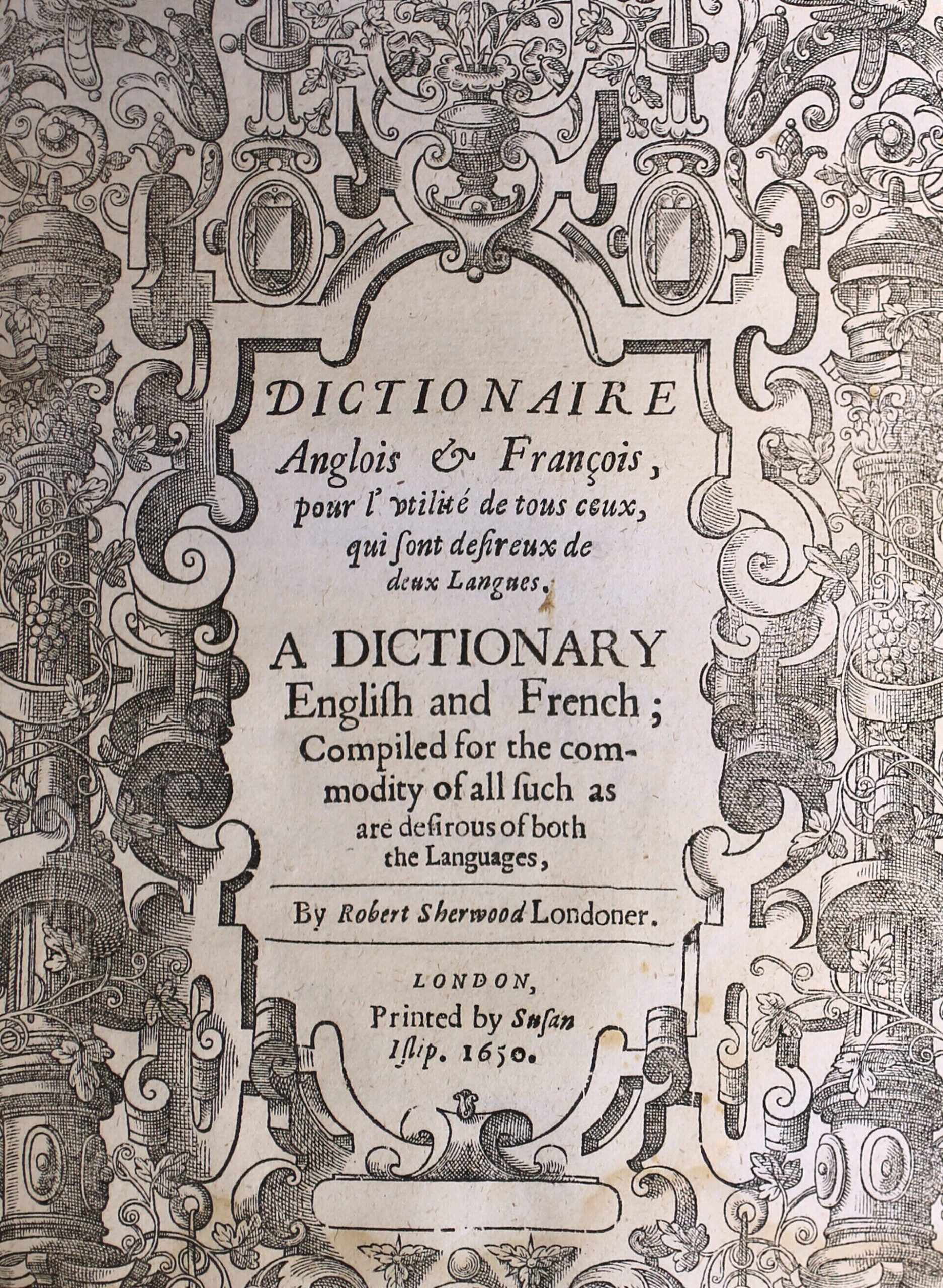

The CCC collects general bibliographical data (authorship, titles, publication dates, format, etc.) for translations printed in the period. Its main added value, however, in comparison with non-specialized catalogues, consists in the identification of source, mediating, and target languages, direct or indirect translators, as well as copy-specific descriptions of the paratextual features of the printed books listed in the catalogue (dedications, addresses to readers, illustrations, indices, marginalia etc.), as available.

It also features short biographical notes for the translators that could be identified.

On this page: Data Provenance | Terminology| Project Team | References

Data Provenance

The main bibliographic source for the CCC is the English Short Title Catalogue. Information about titles, dates, authorship, imprint and format details is derived from it. Descriptions of the paratextual features of individual translations are based on the corresponding entries in the Early English Books Online collection of digital images. Please note that new sets of images are constantly being added to EEBO and that entries are continually being updated as new information becomes available.

Data collection started in 2014 under the direction of Marie-Alice Belle (Université de Montréal) and Brenda M. Hosington (Université de Montréal/University of Warwick). The CCC is the result of many years of iterative, ever-evolving, collaborative work, and we are most grateful for the meticulous and patient effort put in by our research team. The main corpus of the CCC was gathered from ESTC by 2017; the following years have been devoted to enriching this core corpus by tracing languages of translation, identifying translators, and developing copy-specific descriptions of printed translations. The catalogue statistics and map visualizations were developed by Dr Lisa Teichmann, postdoctoral fellow at the Université de Montréal in 2024-25.

Our method for identifying translations in the ESTC combined a number of strategies: title keyword search, using the main roots then designating the translation process (e.g. “translated”, “Englished”, “imitated”, “turned”, etc.); keyword search by language or author name, and other ad hoc strategies.

We followed the principle established in the Renaissance Cultural Crossroads Catalogue according to which only titles in which translated material counted for at least 30% of the contents of the printed book were included. Titles containing short translations (e.g. printed miscellanies, or translations printed together with original poems), were collected as a separate corpus, which we hope to make available at a later date.

Information on translators was gathered from a variety of sources. Existing entries from the Renaissance Cultural Crossroads Catalogue were systematically consulted, and where a translator appears in both the RCCC and CCC a link has been set up between the two entries. The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography also represented a crucial source. We consulted early modern works such as Anthony a Wood’s Athenae Oxonienses and the records of the Stationers’ Company. Finally, we also consulted international resources such as the records of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France or the Virtual International Authority Files.

Terminology

As noted above, the catalogue reproduces the general bibliographical categories of the ESTC (Title, short title, format etc.)

The categories of “source” and “target” languages are those most widely used in Translation Studies – although, of course, a given translation can have multiple sources, sometimes in various languages; in such cases, we have done our best to document them as accurately as possible. Our corpus presents a certain number of indirect translations (that is, translations derived from existing translations in another language). While the RCCC uses the category of “intermediary” translations, translators and languages, we prefer here to speak of “mediating” ones, in keeping with more recent research and publications on early modern so-called “second-hand” translations (Belle and Hosington 2022, 2023).

Similarly, whereas the RCCC offered information on “Liminal” material, we adopt here the broader category of “paratexts” to reflect recent critical discussions in early modern studies (Armstrong 2007; Smith and Wilson 2012; Boutcher 2015; Coldiron 2015; Belle and Hosington 2018). Over the course of our project, we gradually moved towards an inclusive approach and decided to list discursive paratexts (titles, prefaces, dedications, encomiastic poems, etc.), but also visual paratexts (frontispieces, illustrations, decorations, diagrams); organizational paratexts (indices, tables of contents, running titles etc.); and finally, promotional paratexts (mainly in the form of printed “advertisements” for other books sold by stationers). We have also sought, as much as possible, to document readers’ marks in the form of manuscript dates, marginal annotations, name inscriptions (transcribed where readable) and other ownership marks (e.g. bookplates).

It should also be pointed out that the “Notes on translation” do not provide comments on the linguistic or stylistic features of the translations as such. Rather, they focus on bibliographical information imported from the ESTC or features specific to the copies consulted on EEBO (multiple EEBO entries, textual variants, manuscript annotations), or any other particular points of interest (authorship, provenance, circulation, reception, etc.).

Project team

The CCC, its theoretical underpinnings, as well as the accompanying thematic corpora and visualizations were developed as part of two consecutive research projects:

2014-2018: “Translation and the Making of Print Culture in Early Modern Britain (1473-1660)”.

PI: Marie-Alice Belle (Université de Montréal), Co-I: Brenda M. Hosington (Université de Montréal and University of Warwick), Collaborators: Guyda Armstrong (University of Manchester), Warren Boutcher (Queen Mary University London), Anne E. B. Coldiron (Florida State University).

2018-2024: “Trajectories of Translation in Early Modern Britain: Routes, Mediations, Networks”.

PI: Marie-Alice Belle (Université de Montréal), Co-I: Brenda M. Hosington (Université de Montréal and University of Warwick), Collaborators: Guyda Armstrong (University of Manchester), Joyce Boro (Université de Montréal), Warren Boutcher (Queen Mary University London), Anne E. B. Coldiron (Florida State University), Joshua S. Reid (East Tennessee State University), Gabriela Schmidt (Ludwig Maximilian University Munich).

Research assistants:

Olga Stepanova, Daniel Lévy, Faustine Richalet, Marie-France Guénette, Laurence Marion-Pariseau, Joséphine Bywaters

Postdoctoral fellow:

Lisa Teichmann

Website design, management and technical support:

Mary Bella, Hugues Lacroix, Syed M. Hussain

References

Armstrong, Guyda (2007). ‘Paratexts and Their Functions in Seventeenth-Century English Decamerons’. The Modern Language Review, 102 (1), 40–57.

Belle, Marie-Alice and Brenda M. Hosington, eds (2018). Thresholds of Translation: Paratexts, Print, and Cultural Exchange in Early Modern Britain (1473-1660). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Belle, Marie-Alice and Brenda M. Hosington, eds (2022). ‘Delivered at Second Hand’? Mediated Translations in Early Modern Britain. Talking Point section of the Forum for Modern Language Studies, 58 (4), 468-521, doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/fmls/cqac053.

Belle, Marie-Alice and Brenda M. Hosington, eds (2023). Indirect Translation in Early Modern Britain. Double special issue of Philological Quarterly, 102 (2-3).

Boutcher, Warren (2015). “From Cultural Translation to Cultures of Translation? Early Modern Readers, Sellers and Patrons”. In Tania Demetriou and Rowan Tomlinson, eds, The Culture of Translation in Early Modern England and France, 1500-1660. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 22-40.

Coldiron, Anne E. B. (2015). Printers Without Borders: Translation and Textuality in the Renaissance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Smith, Helen and Louise Wilson, eds (2012). Renaissance Paratexts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

We acknowledge the financial support of the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and of the Université de Montréal.